Ideas, Arrangements, Effects (IAE): Reading Space as a System

- Wafa Yahya

- May 30, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: 7 days ago

Much of how we experience space is shaped long before we consciously register it. Everyday practices—such as modes of dress, eating habits, or speech—often stem from embedded systems that quietly regulate behaviour. Space is often seen as a simple backdrop where life unfolds. We walk through rooms, sit in parks, or enter buildings without much thought about how these spaces shape our experiences. Yet, spaces are far from neutral. They are architectural, social, and bureaucratic, and they disproportionately disadvantage certain populations while appearing ordinary, inevitable, or “just the way things are.”

The Ideas–Arrangements–Effects (IAE) framework offers a way to make these systems visible. Rather than treating space as a static backdrop, IAE frames it as an active product of ideas translated into arrangements, which in turn generate tangible and intangible effects.

"Ideas are embedded in social arrangements, which produce effects"

(DS4SI, 2020)

According to DS4SI (2020), conventional classroom settings often illustrate the relationship

between ideas, arrangements, and effects. The physical layout-rows of forward-facing seats-symbolises and sustains a hierarchical arrangement of knowledge distribution, where the lecturer assumes the dominant role and students are expected to be passive recipients.

In contrast, rearranging a classroom into a circular format disrupts the conventional hierarchy and enacts a different idea: that of shared knowledge production and mutual engagement. Here, the arrangement becomes a form of intervention that transforms the effect from constraint to inclusion and openness. (DS4SI, 2020; Bennett, 2010)

Understanding Ideas: The Invisible Foundations of Space

Ideas operate beneath the surface. They shape norms, values, and assumptions that influence how space is conceived and justified. Often, these ideas are so embedded that they are rarely questioned. Even when alternatives exist, dominant systems persist—revealing how deeply entrenched certain ways of thinking have become.

Because ideas are abstract and hidden, they are difficult to confront directly. They are not always written down, yet they govern what is considered appropriate, efficient, safe, or valuable. Over time, they become normalised and resistant to disruption, precisely because they are less visible.

Arrangements: When Ideas Take Physical and Soft Form

Arrangements are where ideas become spatially legible. They overlap to create both order and chaos, shaping how bodies move, interact, and relate to one another. Because of their physicality, arrangements are harder to rearrange; they are embedded not only in space, but in institutional routines and expectations. They include the layout of furniture, pathways, lighting, and even rules about how space is used. Arrangements make ideas visible and tangible. They influence how people move, interact, and feel within a space.

A classroom offers a clear example. A conventional front facing classroom arrangement can contribute to psychological stress, cognitive overload, and feelings of anxiety or isolation among students. This structure exemplifies Jane Bennett's, (2010), notion of thing-power, whereby non-human objects (e.g. chairs) exert influence over human behaviours—more on this topic is in Exploring Harmony in Design: A General Look at Jane Bennet, Taoism, and Architecture and Exploring Thing-Power: Letting Objects Shape Design. This arrangement reflects ideas about authority, control, and individual learning.

In contrast, rearranging the classroom into a circular format disrupts the conventional hierarchy of engagement. It can encourage collaboration and reduce anxiety. Here, the arrangement becomes a form of intervention—one that transforms the space from a site of control into a setting that allows participation, visibility, and shared presence. (DS4SI, 2020; Bennett, 2010)

Arrangements are not just about furniture placement. They also include institutional routines, such as scheduled times for activities or rules about noise levels or how to ask for permission before you speak. These routines reinforce the physical setup and the ideas behind it. Because arrangements are embedded in both space and practice, changing them requires effort and intention.

Effects: The Impact of Space on People and Society

The effects of space are the outcomes produced by the interaction of ideas and arrangements. These effects can be physical, psychological, social, or cultural. They shape how people experience and use space, often in ways that reinforce existing inequalities.

For example, a public park designed with wide, paved paths and benches may seem welcoming. But if it lacks shaded areas or accessible entrances, it may exclude older adults or people with disabilities. The effect is that some groups feel unwelcome or uncomfortable, even if the space appears open to all.

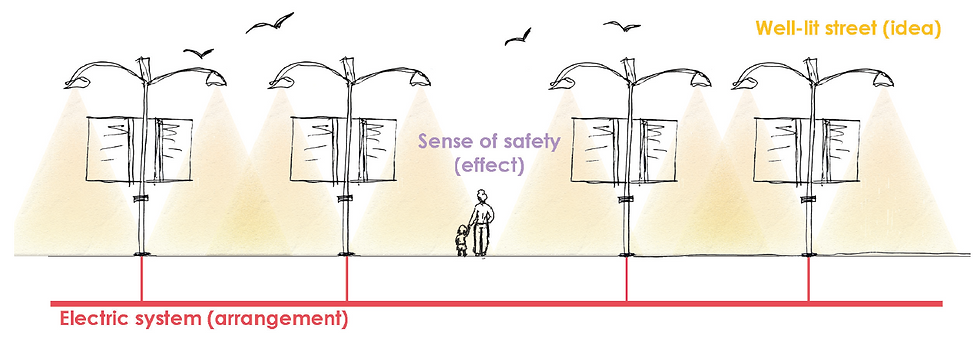

Effects can also be intangible, such as feelings of safety, belonging, or exclusion. A well-lit, open plaza may make people feel secure, while a poorly maintained alleyway may cause fear. These feelings influence how people behave and whether they return to a space.

Reconnecting IAE: Seeing the Whole System

The strength of the IAE framework lies in its ability to reconnect these layers. It provides a lens through which to examine the often invisible systems that shape our environments. Effects do not naturally point to arrangements. They are usually experienced as emotions, habits, or constraints-what feels frustrating, unsafe, or joyful-without a clear understanding of the embedded ideas or systems producing them. This is especially true for marginalised groups like children and caregivers, whose spatial experiences are often dismissed, normalised, or rendered invisible. Isolating arrangements without understanding the ideas that produce them limits the possibility of meaningful change. Likewise, addressing effects without tracing them back to their spatial and ideological origins risks superficial solutions.

Importantly, the IAE framework is non-linear. Effects can spark new ideas, leading to altered arrangements, just as ideas can be embedded into new forms. A well-lit street, for instance, reflects an idea of public safety, supported by an arrangement of electrical infrastructure, and produces the effect of community trust and security. Recognising these feedback loops allows us to move beyond surface-level problem-solving and ask deeper questions: What ideas shaped this? Who benefits from it? Who is excluded?

Urban theorists such as Jane Jacobs, (1961), and analysts like Tomas Pueyo, (2023), have highlighted how many contemporary cities struggle to recreate the vitality of historically successful neighbourhoods. Which leads us to believe that we don't yet understand the ideas or key principles behind these existing good streets. This is especially important when dealing with issues that are repeatedly dismissed, normalised, or overlooked. A “safe” street, for instance, is not simply a matter of surveillance or police presence. It is a layered condition produced through spatial design, social expectations, and political priorities.

Applying the IAE Framework to Rethink Spaces

When addressing large-scale challenges—such as the erasure of play from public environments—it is not enough to mourn what has been lost or to celebrate isolated examples of success. We must ask deeper questions. What ideas are embedded in current planning decisions? What arrangements do they produce? And who experiences the effects?

The IAE framework resists isolating the “social” as a separate realm. Instead, it focuses on interconnected systems, recognising that space is never neutral and that design decisions always carry consequences. Reading space through Ideas, Arrangements, and Effects allows us to move beyond surface-level interventions and toward a more critical, responsible, and humane spatial practice. It encourages questioning the ideas behind design choices and arrangements, examining how they support or challenge those ideas, and observing the effects on users. In this view, a city is not a fixed entity but an assemblage of ongoing interactions.

Practical Steps to Use IAE

Identify dominant ideas:

What assumptions guide the design? Who benefits or is excluded?

Analyse arrangements:

How does the physical setup reflect these ideas? Are there alternative layouts?

Observe effects: What are the real impacts on different groups? Are some people disadvantaged?

Experiment with change: Test new ideas and arrangements to create more inclusive, supportive spaces.

Example: Rethinking a Library Reading Room

Traditional library reading rooms often have fixed desks arranged in rows, promoting quiet individual study. This reflects the idea that learning is solitary and silence is necessary. The arrangement can create stress for those who prefer group work or need breaks from concentration.

By applying IAE, designers might introduce flexible seating clusters, standing desks, and sound-absorbing materials. These changes challenge the idea of silence as the only productive environment and create effects such as increased collaboration, comfort, and accessibility.

Why Seeing Space as a System Matters

Viewing space as a system helps reveal how design choices are never neutral. They carry values and power dynamics that shape who belongs and who is left out. The IAE framework makes these systems visible and open to change.

This perspective is crucial for creating environments that support diversity, equity, and well-being. It moves us from accepting spaces as fixed to seeing them as adaptable and responsive to human needs.

REFERENCES

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant Matter: a Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press. https://www.paradigmtrilogy.com/assets/documents/issue-02/jane-banette--vibrant-matter.pdf

DS4SI. (2020). Ideas, Arrangements, Effects : Systems Design and Social Justice. Minor Compositions. https://www.minorcompositions.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/iae-web.pdf. Design Studio For Social Intervention.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Vintage Books. https://www.petkovstudio.com/bg/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Death-and-Life-of-Great-American-Cities_Jane-Jacobs-Complete-book.pdf

Pueyo, T. (2023, August 6). How to Make Cities Safe. Tomaspueyo.com; Uncharted Territories. https://unchartedterritories.tomaspueyo.com/p/how-to-make-cities-safe?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

Comments